Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh’s first job was working in the Hague branch of an international art dealing firm, Goupil & Cie. It was 1869 and he was just 16.

He was reasonably successful in the firm so he was then was transferred to the London branch in 1873 and then later to Paris. However, he lost interest in the role, which led to his dismissal in 1876.

Following this, he briefly became a teacher in England, and then, deeply interested in Christianity (his father was a Protestant Minister), a lay preacher in a mining community in southern Belgium. He was also dismissed by the church, but his future artwork was heavily influenced by his spiritual beliefs.

Largely self-taught, van Gogh began his study as an artist by meticulously copying prints and studying nineteenth-century drawing manuals and lesson books. He believed that it was necessary to master working with black and white before working with colour, and that it was important to concentrate on learning the rudiments of figure drawing and rendering landscapes in correct perspective.

Van Gogh’s admiration for the Realist Barbizon artists, in particular Jean-François Millet, whose work he’d seen in London, influenced his decision to paint rural life. During 1884 – 85, while again living with his parents in Nuenen in the Netherlands, he painted more than forty studies of peasant heads, which culminated in The Potato Eaters. Van Gogh wrote that he wanted to express that they “have tilled the earth themselves with the same hands they are putting in the dish”.

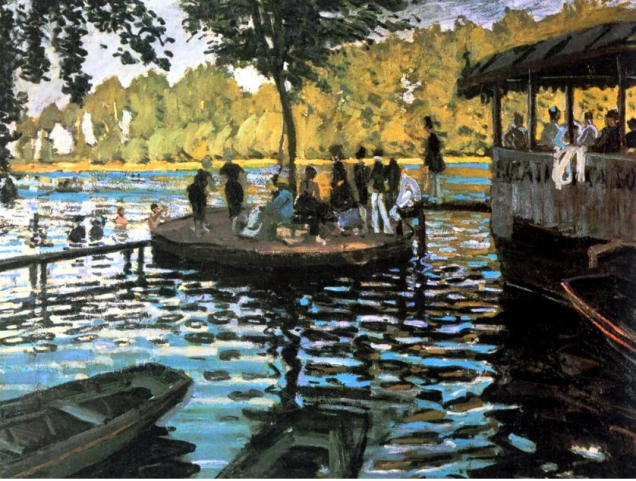

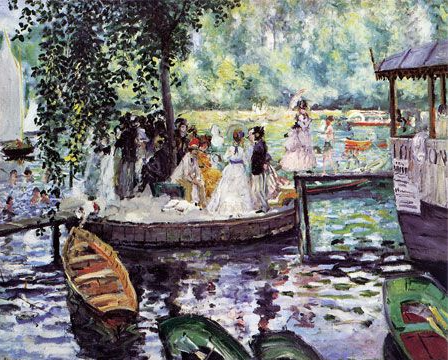

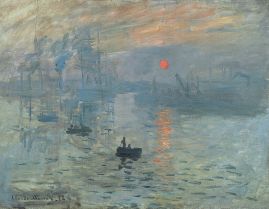

His style underwent a major transformation during a two-year stay in Paris from 1886 to 1888. During this period he took lessons in the studio of Fernand Cormon – an artist who was very popular with foreign students. It was here that he met fellow students Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Emile Bernard. Vincent’s brother Theo was by this time the manager of Goupil and Cie in Paris, and he was able to introduce Vincent to the light filled work of prominent Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. Vincent also saw the latest technical innovations (pointillism) by Post Impressionists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac.

Vincent discovered a new source of inspiration in Japanese woodcuts, which sold in large quantities in Paris. Both he and Theo began to collect them. The influence of the bold outlines, cropping and colour contrasts in these prints showed through immediately in his own work.

He used brighter colours and developed his own style of painting using short brush strokes. The themes he painted also changed, with rural labourers giving way to cafés and boulevards, the countryside along the Seine and floral still lifes. He also tried out more commercial subjects, such as portraits. However, Vincent mostly acted as his own sitter, as models were relatively expensive, and he painted more than twenty self-portraits.

By 1888 Vincent began to tire of the frenetic city life in Paris. Unfortunately his mental health began its decline, resulting in violent mood swings, depression, and drunken and erratic behaviour. He longed for the peace of the countryside, for sun, and for the light of ‘Japanese’ landscapes, which he hoped to find in Provence in the South of France, and so in February 1888 he moved to the “little yellow house” in Arles.

He hoped his friends would join him and help found a colony of artists. Paul Gauguin did join him for a short period of time, but with disastrous results. Van Gogh’s nervous temperament made him a difficult companion and night-long discussions combined with painting all day undermined his health. It was at this time that he cut off part of his left ear with a razor. Penniless, he spent his money on paint rather than food, living on coffee, bread and absinthe.

His ongoing depression caused him to seek periodic refuge in a nearby asylum at St Remy. Over the course of the next year, he painted some 150 paintings, including many still lifes and landscapes. He also painted copies of works, using black-and-white photographs and prints, by such artists as Delacroix, Rembrandt and Millet. He described his copies as “interpretations” or “translations”, comparing his role as an artist to that of a musician playing music written by another composer.

In May of 1890, his mental health appeared to have improved and he moved to Auvers-sur-Oise under the watchful eye of Dr. Gachet. Two months later he was dead, having reportedly shot himself “for the good of all”.

Van Gogh’s finest works were produced in less than three years – in a technique that grew more and more impassioned in brushstroke, in symbolic and intense colour, in surface tension, and in the movement and vibration of form and line.

During his brief career he sold only one of his paintings. However, by 1890, van Gogh’s work had begun to attract critical attention. His paintings were featured at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris between 1888 and 1890, as well as in Brussels in 1890, and articles about his work began to appear in major newspapers.

Read more, and see a full range of images at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en.

This blog is just a short excerpt from my art history e-course, Introduction to Modern European Art which is designed for adult learners and students of art history.

This interactive program covers the period from Romanticism right through to Abstract Art, with sections on the Bauhaus and School of Paris, key Paris exhibitions, both favourite and less well known artists and their work, and information about colour theory and key art terms. Lots of interesting stories, videos and opportunities to undertake exercises throughout the program.

If you’d like to see some of the Australian artwork you’ll find in my gallery, scroll down to the bottom of the page. You’ll also find many French works on paper and beautiful fashion plates from the early 1900s by visiting the gallery.